Élian's portrait, finished and framed.

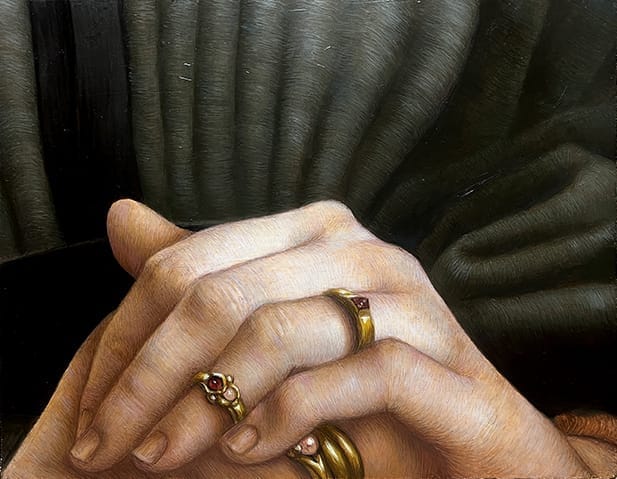

The Bronzino portrait of Eleonora di Toledo and her son, Giovanni that Élian was fascinated by. He still spends time with it whenever he comes for a visit.

This is another piece that Élian and certain other birds seem to respond to as if they understand the concept of a devotional painting.

I was wrestling with this study of a Justin Wood still life when Élian came the first time. Justin's an amazing painter and kindly gave me permission to do this piece, which was way more difficult than it appears.

Chapter 1 of Élian's Tale

Élian, the first to ask

Painter’s annotations in italics. Artist’s note: these paintings are still in progress.

He was the first. (At least, the first I saw.)

I hadn’t fully moved in. The floors still creaked in new tones. The walls smelled like fresh paint (the wall kind). Light spilled softly through the tall west windows and, in late afternoon, left long, unforgiving streaks across the floor and walls.

(I remember thinking the windows made me feel watched. Now I leave them open a crack, even in winter.)

The sitting wall was just a wall needing plaster. It wasn't even an idea. Just an uneven surface opposite the window glass where rusted screws were stuck to the plaster and lathe like barnacles. I was pretending to work on a painting of two green apples, after a Justin Wood still life, trying to work out a new way of applying paint. But in my head I’d already wandered. For some reason my mind had drifted toward birds.

They were poor sketches. Mostly imagined. All wrong in one way or another. I’d tried painting one — a small bird, yellow — using cadmium yellow, then lemon yellow, then a low chroma ochre. Every mix rang false. (There’s nothing quite like failing at yellow. It humbles you, rather loudly.)

I gave up halfway through the wing. Maybe I turned back to the apple. Maybe I didn’t. What I do remember, clearly, is this:

A small shadow passed across the lower pane. I thought it might be a large moth. I didn’t look up. But then, light as breath on silk, he appeared on the window sill.

A single American Goldfinch. Male. In full breeding color, though the season was wrong. So was the hour.

He didn’t land. He hovered. (I didn’t have language for that yet. Not for a bird hovering like a thought you haven’t heard.) Wings taut, just above the old shelf. Others would perch there in time, but he didn’t. He hovered like a question. Not one for me, exactly. One for the room.

He held the pose a moment longer, then dropped lightly to the far end of the windowsill. Near the ficus tree, not the canvas. He didn’t approach. Didn’t glance at me. Instead, he faced the wall.

And stared.

At the Bronzino print — one of the only framed images I’d unpacked. A noble woman in velvet, unsmiling, composed, unreal. She watched the room from the edge of the frame like someone trying not to be noticed. (I’d hung her there without thinking. Meant to move her. Never did. I still have that print, but she stays in a drawer now.)

Elian didn’t blink. His body lifted slightly with his breath, but he didn’t shift. Just stared at her. At her portrait. Then he turned — just a bit — and gave a single, dry tick. That was all. No flutter, no chirp. A single sound, like judgment passed on something premature. He left soon after. Just as softly as he’d come.

(At first I thought I imagined it. I even checked the palette. Still open. Paint drying along the edges. Yellow still wrong.)

He didn’t return for several days.

But he had changed something. The room held a trace of him. And the Bronzino no longer felt like just an old painting on the wall — it felt like a comparison.

When he returned, I was ready to be less foolish. I unlatched the sash and raised it a hand’s width — an invitation more than an opening. He waited, measuring me the way a chapel measures footsteps. I stepped back, palm open. He slipped in — quick, bright, decisive.

He danced then, a little untranslatable circuit: a hop to the lemon pot, a dart to the brush jar rim, a light-footed slide across the palette table where he avoided every wet passage as if he knew the dangers of haste. A turn. A bow (I think). Then he zipped to the uneven shelf that would later become the sitting wall and settled, balanced like a coin at the moment of choosing.

And I — always hopeful — reached for a pencil. (I thought he wanted to be drawn. But he was waiting to see what I’d learned.)

He didn’t move. Didn’t blink. But I knew better than to copy the earlier pose. This was not the same moment.

I began again, slowly, trying to feel my way forward. I laid down Cadmium Light, just a whisper of it, hoping maybe I’d gotten closer, and he lifted his wings. Not to fly. Just a warning.

I scraped the color off.

He stayed. That was the beginning.

45% OFF DECEMBER SALE | Discount Code DEC45 Has Been Applied To Your Current Visit

Bird Portrait Collections

Contact

Have a question, an issue with your order, or just want to say hello? My email is richard@richardmurdock.com

Read new Avian Chronicles stories by staying connected via our emails and social media.

All Content © Copyright 2025